Seeing Stress With Supercomputers

Technology Networks | December 07, 2018

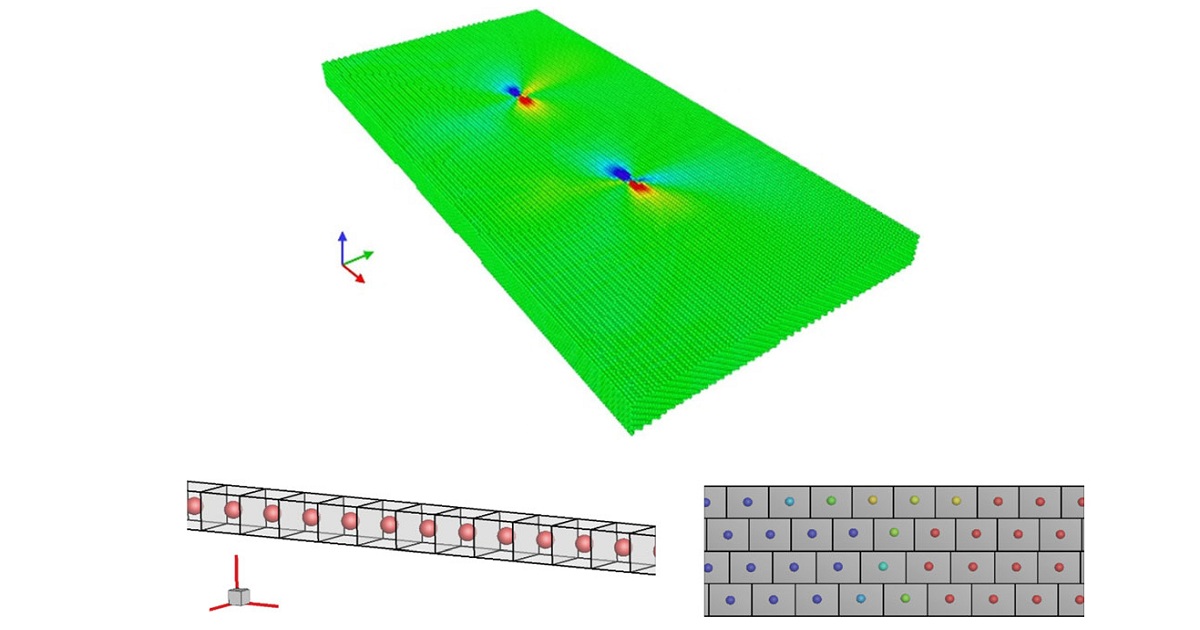

Supercomputer simulations show that at the atomic level, material stress doesn't behave symmetrically. Molecular model of a crystal containing a dissociated dislocation, atoms are encoded with the atomic shear strain. Below, snapshots of simulation results showing the relative positions of atoms in the rectangular prism elements; each element has dimensions 2.556 Å by 2.087 Å by 2.213 Å and has one atom at the center. Credit: Liming Xiong.

It's easy to take a lot for granted. Scientists do this when they study stress, the force per unit area on an object. Scientists handle stress mathematically by assuming it to have symmetry. That means the components of stress are identical if you transform the stressed object with something like a turn or a flip. Supercomputer simulations show that at the atomic level, material stress doesn't behave symmetrically. The findings could help scientists design new materials such as glass or metal that doesn't ice up.

Xiong and colleagues treated stress in a different way than classical continuum mechanics, which assumes that a material is infinitely divisible such that the moment of momentum vanishes for the material point as its volume approaches zero. Instead, they used the definition by mathematician A.L. Cauchy of stress as the force per unit area acting on three rectangular planes. With that, they conducted molecular dynamics simulations to measure the atomic-scale stress tensor of materials with inhomogeneities caused by dislocations, phase boundaries, and holes.